Dear reader,

When I showed up at Brown for my MFA, I felt wildly unprepared and out of my element. I had always considered myself smart, but I wasn’t used to the way that people at Brown spoke, and I had never heard of the things they often spoke about. I came to understand that a lot of this was intellectual posturing, though, to be clear, much of it was substantive and worthwhile as well. Regardless, people were saying things that I had never heard before as if they’d been saying them their whole lives. I was grateful that the first year of the degree was on Zoom, so that I could sit in my little office and type things people said into google phonetically, trying to parse meaning from their conversations in that way.

One of the buzzwords that it took awhile to fully grasp the meaning of was ‘archive.’ People seemed to be referring to the archive, but they didn’t mean any specific thing. I was confused by this and searched for more information, reading essays about the archive, trying to understand what exactly it meant. Now, I’ve come to grasp it in my own way, which I hope is the way that others understand it as well — the archive is the written record; it’s the canon; it’s the collective knowledge base, narrow, as it is often written by those, I have to say, intellectual elite that I sometimes found myself among at Brown and whose exclusive club I try hard not to join.

I’ve come to love Saidiya Hartman’s work on the archive. It’s her essay, Venus in Two Acts, that I think really clued me in. I tell pretty much everyone I meet to read it, and I’ve read it myself probably a dozen times, though (as with all good essays) there are still things I don’t understand.

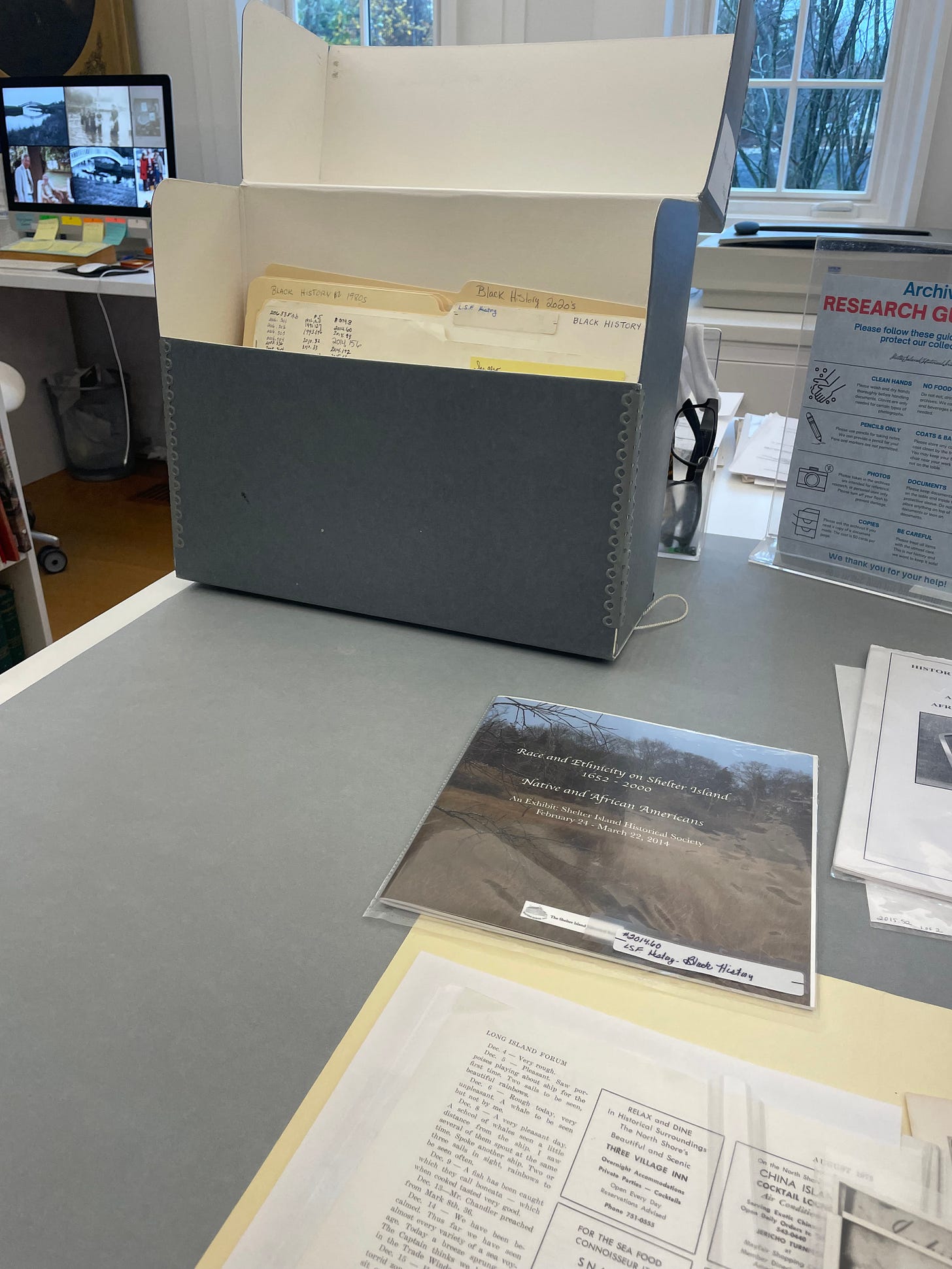

On Shelter Island, the archive is referring to something much more specific: the boxes of information gathered at the Shelter Island Historical Society. I emailed in advance about checking out some of their collections, particularly those on Black and Indigenous history on the island. The archivist, a fellow young millennial, agreed to set up a meeting. I arrived at our scheduled time, nervous and uncertain what to expect, almost thinking that I was about to be quizzed on my own knowledge of the island’s history.

Waiting for me was a modest little history center that was being decorated for a Black Friday sale of local artists’ work. Flitting back and forth between the volunteers, all of whom were over the age of 60 (as are most people on the island), and me, the archivist pulled out a box labeled Black History.

This is it — all of the documents and information, compiled in one box that isn’t even half-full. Some of the file folders contained fewer than five documents, while other documents were repeated several times throughout the folders, such as an article that was written in the 70s by (coincidentally) another Helen about the enslaved people on the island and was subsequently published in various outlets over the decades, being printed and put into the folder each time.

This archive has been touched by few hands; you see the same names coming up again and again, notes from just a handful of researchers. “Thought you’d like to see this,” “let’s put this in the Black History folder,” etc. I like one historians suggestion of creating a new folder for an enslaved man, Obium, whose name comes up fairly often — though his folder would still be woefully slim.

This helps contextualize, I think, what is meant by the archive. The documents in these files were mostly quite repetitive, with the same information being gone over again and again. The primary sources were fascinating, such as the manumission papers for the last enslaved person on the Island, London.

There’s a document that traces the familial history of Jupiter Hammon, the first published African American poet, back to Nigeria, which gives the best indication I’ve been able to find of where the enslaved people at Sylvester Manor came from. There’s a note about retrieving a horse that Obium “ran away with” — the focus being more on the horse, as Obium has been captured by this point and the concern is elsewhere.

Overall, the pickings are slim, the information scant. While Sylvester Manor itself still stands, the earth is still being cultivated and farmed and loved, the people who were forced to work it centuries ago, who made the Sylvesters’ wealth with their forced labor, are mostly ghosts.

I’m grateful for the information that I was able to find, and any glimpses into the past are exciting, if also harrowing at times. I’ll be turning everything over in my mind for some time to come, as with everything I encountered on this trip. The stories of these people are not mine to tell, nor really, I don’t think, mine to share, at least not in my own words — the story that belongs to me is the story of the Sylvesters, their ancestors, their descendants, their deeds. But to try to tell their story without a depth of understanding about their surroundings, the world they lived in, the people whose lives they affected, feels deeply irresponsible.

Take, for instance, a book I found in the inn I’m staying at. It was published in 2002 for the island’s 350th anniversary. In it are photos and histories. The way the story of the original inhabitants is told is somewhat clipped — sharing some information and ending with the deeply passive, “Gradually by the late 1700s, many of the Shelter Island Manhansets were absorbed into the culture of the European settlers.” There are no mentions of the land deals that were made and not honored; the Europeans’ taking over of the island’s natural ecosystem, forcing an economy based on production and payment (in the form of Barbadian rum); the European diseases that wiped out vast portions of the Native population; the forced dependance that Sylvester Manor created.

Similarly, the book mentions the enslaved people only in passing. While writing about what Grissell, the lady of the manor, would do in her day to day life, it places her into a position of cooking, cleaning, and gardening at certain points, while then acknowledging that the labor was “primarily performed by slaves brought from the West Indies and by indentured servants from England, supplemented by Native Americans.” (An Island Sheltered)

Another book that I found, The History of Shelter Island by Ralph G. Duvall, laments on its very first page, “What a pity it is that the Indians who inhabited the territory now known as the United States have left no written records of their race.”

Meanwhile, I uncovered whole documents (in another file — the Native American file; equally slim) on the dying Algonquian language, which will be a story for another day.

As a storyteller and a history lover, I find a few questions to be key. How do I relate history in an appropriate way? How do I avoid recreating old harms or introducing new ones? How do I produce writing that is aware of itself and its position, which tells only the story I am able and ought to tell? How, and at what times, do I move aside for other voices?

We’re all history tellers, is the truth. We tell our own stories. We talk about the lives of our parents, our grandparents. We speak broadly about the past in casual ways that we may not have examined. I think, in these instances, the above questions are still just as pressing.

I’ll continue to grapple; I hope you do, too.

All sources thanks to the Shelter Island Historical Society.